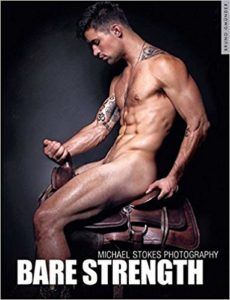

Many of the authors and publishers I interviewed mentioned the success of Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls—which has two of the three most-funded publishing projects on Kickstarter—as a beacon of success on the platform. Curiously, no one mentioned the second-most funded Kickstarter book, Chassepot to FAMAS, a detailed history of French military rifles, which started with a $25,000 goal and ended up raising over $800,000. What makes an author or publisher decide to use Kickstarter to launch a book, rather than pursuing a more traditional model, whether it be trade or self-publishing? For Greg Stolze—an author who has published both traditionally and through the normal self-publishing process—it was a combination of time and money. He said trade publishing can be “glacial,” but Kickstarter has an advantage over self-publishing because “people have a motive to act right away.” He’s not alone in that reasoning. For The Golden Ratio, author Jen Golbeck said they “wanted to turn this over faster. I wanted Ellie, the illustrator, to get some pay for her work before we published.” Photographer Michael Stokes decided to do his first Kickstarter for Bare Strength in cooperation with the publisher for his previous book via a profit-sharing model. Rose Fox and co-editor Daniel José Older came up with the idea for Long Hidden after a twitter conversation. “Bart Leib of the small press Crossed Genres then got in touch with us and offered to make it happen,” Fox said. “The Crossed Genres business model was based on up-front Kickstarters followed by POD [print on demand] and e-book sales. So it was crowdfunded traditional publishing, not self-publishing—a hybrid model. The authors and artists were paid up front, and Daniel and I got up-front payments and then royalties on further sales.” Glenn Hauman, VP of Production at ComicMix, said they fund some but not all of their projects with a crowdfunding model. They use the platform when they “want to make sure there’s enough of a market to support the costs involved and we want to reach out to a different audience than just the comic shops and bookstore buyers.” Two interesting examples are Mine! a comics collection to benefit planned parenthood and Song of Giants: the poetry of pulp. Chao is pursuing both traditional publishing and self-publishing in order to diversify. She turned to Kickstarter because, “It’s important to me that my self-published work is of the same calibre as traditional publishing. The only way to do that is to emulate the same process. With Kickstarter, I don’t have to compromise the heart of my story. I have full artistic autonomy to ensure all aspects of the book are the best they can be, and packaged in the most appealing way possible.” After deciding to dip their toes in the self-publishing waters, authors Kate Karyus Quinn, Mindy McGinnis, and Demitria Lunetta came up with the concept for Among the Shadows. “We thought people would want to read an anthology of scary stories from already established authors,” Lunetta said. “So instead of paying all the start up costs out of pocket, we gave people the opportunity to buy in and receive early release copies.” They were right and the project funded in just two days. Since their first project was so successful, the authors behind Among the Shadows conducted a second successful campaign for another anthology titled Betty Bites Back. Tobias S. Buckell was introduced to me as one of the first authors to successfully fund a book Kickstarter. He turned to the platform to publish The Apocalypse Ocean, the fourth book in a series published by Tor. “I’d been watching authors and other artistic types use Kickstarter to good affect. And the powerful part of it was the ability to test your potential market. Kickstarter took pledges (or pre-orders) from everyone, and … I knew then that this was a way to try something different,” he said. Chao agrees. “If it’s not a product that resonates with readers, then it won’t sell. It’s a good litmus test.” Harry Connolly put his second series up on Kickstarter after his first series didn’t garner the attention his traditional publisher had been hoping for. “I had seen other authors turn to Kickstarter, but wasn’t sure I could bring myself to ask readers directly for the money I needed to finish the books. Then I saw Amanda Palmer’s TEDTalk on asking, and turned myself around. Ms. Palmer might not be the internet’s favorite person, but she did a lot of good for me with that talk. I set a goal of ten thousand dollars and, against my every expectation, reached it in eight hours.” Most of the authors I spoke to had some campaigns they looked to as an example of success, but some did more research than others. “I did a lot of research, comparing the many successful Kickstarter campaigns and saw they had many similar traits,” Chao said. “Clear concise descriptions … as well as desirable rewards.” Lunetta came to similar conclusions. “The Kickstarters that were clear and seemed likely to deliver, were the most successful so I was sure to model ours on those.” Before using Kickstarter for his book projects, Stolze had used the platform to crowdfund the game Meatbot Massacre and so he had some experience with running campaigns. “No two are alike, and so each campaign has to be tweaked,” Hauman added. Golbeck didn’t look at other projects when setting up her Golden Ratio campaign, but she did turn to an unlikely source for advice. “Dan Sinker’s Robert Mueller and Pee Tape prayer candle Kickstarter was one of my favorites that I supported, and I remembered his description of his experience with fulfillment in that. We don’t know each other, but I randomly emailed him and asked for advice. He was so generous with his time and sent me a very long response with invaluable advice on how to handle this. I would have been lost without his help.” Connolly came up with an interesting model for his second Kickstarter, which was a part of their “Break Kickstarter” campaign that encouraged creators to use the platform in creative ways, so he had no models of success for that project. He decided to use it to gauge reader interest in a continuation of his Twenty Palaces series, which the publisher had abandoned. “I told backers that I would write a sequel, and that they would determine how long the stories would be. They could pay me at five cents a word. A five dollar pledge was worth a hundred words.” He set a minimum of $500, “which would have been a sweet little novelette, and probably the minimum word length I could manage,” and capped it at two novels after feeling like he over-promised on his first campaign. This project funded for $17,286, which will pay for two hefty novels, the first of which he’s currently writing. As an author myself, the idea of crowdfunding a novel terrifies me a bit. My worry is that I would put it out there and promote it the best I could and that nobody would notice or care. “Of course that’s always a risk,” Chao said. “Though I had a relatively modest goal (£3,200) I was worried I may not reach it. Nothing is a sure thing.” Stolze agrees. “Of course I was concerned. People are unpredictable, wages are uncertain, and there’s a lot of competition for the entertainment dollar.” Buckell was pragmatic about the possibility. “That’s always a risk with doing it in public,” he said. “However, I think I’m used to rejection and failure because it’s a part of the process of striving to be living the creative life. Failure as an artist means I tried something, and it’s only when we stop trying things that we drown, I think.” Creators who already had a strong online following weren’t as concerned. “I expected the fans would be into it,” Golbeck said. “But I’ll add that I think our situation is sort of unique, as we are leveraging a really strong online presence rather than trying to build enthusiasm through the Kickstarter.” “In addition to having an extremely awesome concept,” Fox said, “we invited a lot of well-known authors to submit stories, and we had a lot of fun perks for backers, like getting hats autographed by me and Daniel. He and I had extensive social media networks and worked them hard, so we got some very popular people tweeting about the project and otherwise spreading the word.” Michael Stokes, with his work being visual and striking, had amassed quite a fanbase before his first Kickstarter. “I thought I’d make it,” Stokes said. “I didn’t think I’d make it in one day.” I personally backed his second Kickstarter, which was wildly successful with 3,500 supporters for a total of $411,000. Stokes said in the first couple of days, “I posted something on social media, and it got the attention of this guy from MTV who follows me. He saw how excited people were. So he wrote an article and then Bored Panda, and then everyone…they started linking to the Kickstarter.” Connolly had a different mindset on his second by-the-word campaign. “By setting the goal so low,” he said, “I made sure the campaign was not centered on the question “Will this fund?” Almost from the start, the question for this project was “How much fiction will we get?”” I asked Hauman what he would do if one of his projects didn’t get funded. “Weep, wail, gnash our teeth, rend our garments,” he said, “and either move on to the next thing or figure out how we can make this work better.” I have a theory that books with graphic elements are a bit easier to market and fund via crowdfunding. “It absolutely helps,” Hauman agrees. “We do comics and graphic novels, so art is part of the package. But even for prose books, some imagery is helpful to connect with readers and backers. There aren’t a lot of newspapers that only run text on their front page, after all.” Since they hit their stretch goal of $30,000, every story in Long Hidden was accompanied by an original piece of art. “It was a significant work that mattered a lot to a lot of readers and made a strong point in the industry about there being a market for SF/F by and about marginalized people,” Fox said. “Long Hidden alums have gone on to do amazing things—we can’t take credit for Sofia Samatar‘s novels making such a splash or Ken Liu becoming a star of Chinese Sci-Fi translation or Troy L. Wiggins co-founding FIYAH, but we can say we knew them when.” For writers looking to launch their own Kickstarters, the authors I spoke to have some advice on promoting your campaign. “I have a newsletter with 1400+ subscribers, which is my primary tool for contacting readers,” Connolly told me. “There’s also my social media, but the effect there is limited. By far the best promotional tool has been my readers themselves. The best promotion is always done by people who are not me, not related to me, and are spreading the word solely because they’re enthusiastic about my work.” Stolze also relies on his newsletter, Twitter, and cross-posting to previous campaigns he’s run. Stokes concurred. All the authors I spoke to indicated they would continue to use Kickstarter to fund future projects. “Kickstarter has serious street and professional cred,” Chao said, “and I liked that it was populated with amazing creatives making amazing things. I’ve backed a few projects myself and it’s really a great way to be at the forefront of exciting products. For me, it was the perfect fit.” For the purposes of this article, I chose to focus on projects that had been successfully funded on Kickstarter, but there are of course many book-related projects that don’t get funded. There are also other platforms available. Unbound is a UK-based crowdfunding publisher that has “commissioning editors” who sort through projects and help with the process—for a 50% cut of profits as well as costs. Many writers also choose to use Patreon, GoFundMe, and Indiegogo to fund their projects and these alternative models are becoming more and more popular as the publishing industry expands and changes.