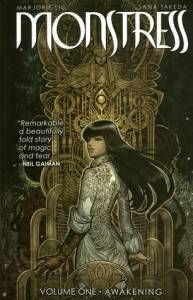

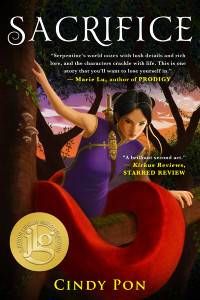

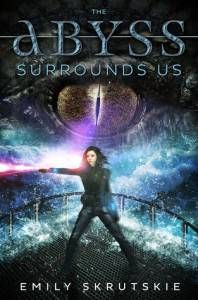

These days, however, I am loving referring to myself (privately, at least) as a monster woman. The status quo for what a human woman should present herself as—the fact that she has to present herself at all—is unacceptable. It’s rigid, cruel, and kind of boring. Monsters have fewer rules. And I’ve found that I’m drawn to the kind of female characters who, either figuratively or literally, have to wrestle with the human/monster dichotomy and find a way to get comfortable with themselves. See, I do that every other day. Reading these characters helps me sort out my own problems. Of course, in fiction, getting comfortable with one’s monstrosity isn’t always for the best. For the people around you, I mean. Characters like Queen Levana from The Lunar Chronicles by Marissa Meyer and quite a few of the female characters in Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda’s Monstress, do some pretty unforgivable things—but no one could ever say these women are “proper,” or that they are anyone’s first description of what a girl is like. These characters may be able to organize the most perfect tea party, but you might want to get someone else to taste that tea first. And then there are the kinds of monster girls I could read about forever, like Adelina Amouteru from The Young Elites series by Marie Lu. She may belong with ladies I’ve mentioned above, but I still feel like she has the chance for redemption. Her descent into villainy is so interesting because she hadn’t been monstrous to begin with. She was just different and for that she paid dearly … and now she makes others pay. Call me callous, but I root for her. Skybright from the Serpentine duology by Cindy Pon is another character that could have had the same character arc as Adelina, but Pon’s writing is surprising and she chose to go a different direction. It’s true that Skybright has to deal with being half-serpent, a giant one, often making people uncomfortable with surprise nakedness—only a plus in my books—but the thrill and disgust that other people feel for her fades somewhat into the background in the sequel novel, Sacrifice. Skybright is too busy saving the world and understanding her sexuality to care much about other people’s conflicted feelings about her. Not that it doesn’t hurt when people (unwittingly) do or say hurtful things, it’s just that she is better equipped to heal herself. Lady Fire from Kristin Cashore’s Fire is another such character. One of my recent favourites, however, is Cassandra Leung from The Abyss Surrounds Us by Emily Skrutskie. She has a heart of gold, but after she is kidnapped, held hostage, and is generally traumatized, she finds that gold is much too malleable a metal. She isn’t less or more of herself by the end of the first book, and I can’t presume to know where her story is headed, but Cassandra is definitely much more resilient than when she started off. In the end, monstrosity and humanity is only a conversation for beholders to have; for these characters, “monster girls” merely offers more freedom to grow in strange and lovely ways, and in some cases, to exist at all. To me, “monster girls” is just a fantasy take on the “bad girls” trope and that’s why I love it. These characters misbehave, they don’t smile unless they want to, they’re loud, they’re large, or not—above all else, they’re whatever they want to be.